from Bernd Fischer – jugend-kultur-kirche-st-peter Frankfurt/Main.

The question of who I am – which cannot be answered without answering the question of what the world is, is one that has always accompanied me. It is a desire I am driven by which depend on my mood could be either arrogant or recklessly naive. Time and again I find reassurance in art which – in light of the question posed – has become the central place where I grapple with this.

About this I can tell you something which may facilitate your understanding of my picture.

Art, the way we refer to it in Europe today, the kind which is represented in museums, in public, semi-public or private collections, is for the most part art from the period after the birth of Christ.

The appreciation of art in our culture is unthinkable without the architecture, sculpture and paint-ing which was commissioned by different churches. Giotto’s, Michelangelo’s, Riemenschneider’s or Grünewald’s works would be inconceivable were they not commissioned by the church.

In contrast to myself these artists were commissioned to work on a specified obligatory content agreed on by societal consensus and therefore comprehensible to most people. The artists came up with and attended to pictures whose content was generally understood.

During the course of history, and related amongst other things to the decline of religious com-munities as commissioners of work, content which most people in this cultural circle understood, gradually disappeared.

Artists responded by making art the subject of art. For me this development is very interesting and one which I value as a contemporary artist faced with this challenge.

What I cannot so easily accept here is the exaggerated self-referentiality and thus the isolated position in society to which this has lead .

In the middle of the last century, Ad Reinhard, an American painter, reproduced this program-matically by stating: “Painting is painting and everything else is everything else.”

This radical parting of art and life I find convincing in this historical context and in this artistic development.

My own position, however, differs.

For me a picture is always also a picture of something. We are more or less able to see the visible aspects of life. As a painter I work with colors and shapes which are perceived by the eyes in the same fashion as for instance an apple or a snake is perceived. An apple can be eaten. A snake can bite. But what is a picture capable of? You may say that a particular style or artwork means something or nothing to you, that it is your taste or not as the case may be. A color may be lovely or biting. The combination of apple and snake evokes different associations among people of this cultural circle than would a chicken and an egg.

As a painter I work predominantly with colors and shapes. This is the truth of the medium.

How, and in which way I articulate shapes and colors, however, is a question of artistic intention. In other words, a question which touches upon the artist’s self-understanding. Alberto Giacom-etti, one of the titans of 20th century art said sometime in the first half of the 20th century, “The first task of an artist is to identify and determine his own standpoint.” The way I understand it this sentence holds true even today, without alteration, and it will probably turn into a historical one only once the position and function of art in society has changed.

What stories can pictures tell? What content can be summed up in pictures if there is no gener-ally binding – or at least generally comprehensible – content anymore?

The Egyptian pictorial works created between 2,400 and 5,000 years ago in a very different func-tional context than today’s art combine within themselves the representation of a complex nature perceived in a variety of ways and the question of connections between the individual and the wholeby Bernd Fischer – st. peter’s youth culture church, Frankfurt/Main

Designing what the artist refers to as a “heartroom” in Saint Peter’s was a complex undertaking. On the one hand, the room was to be used as a place for tranquility and meditation, on the other it was to be used by groups of up to 45 people as a venue for church services

In addition, the former dedication of the room as a gallery to the church, had to be taken in to account in the new concept. On the left, as seen from the entrance, are three long, ascending, step-like seating rows. Behind them a long strip of old, somewhat dreary-looking church windows. This made it clear that the room had to function from a crosswise perspective.

Bernd Fischer decided on a satinised glass door as the entrance to the stairway, with verse from the bible applied to both sides. With its various lighting effects outside and inside it looks like a membrane between the everyday happenings in the stairway and the “holy space” inside. “The floor is basic and of primary importance, physically and psychologically.” Following his words, the artist designed the floor in solid oak. In line with its ability to withstand, as understood in the gospel, he also had the altar built in the same oak (1m x 1m x 1m), “arising from the earth” in the middle in front of the seating rows as the central focus of the room. The three seating rows are cushioned in the colors yellow, red and blue “so that one is able to lie on yellow, red and blue.” Left above the altar is a cross designed by Bernd Fischer. For more individual use, the artist ingeniously designed a separate special center on the side opposite the entrance. Here he placed four tracks of different lengths for lighting candles. Their light creates a first impression when you enter the room.

In Classical Greece different ideas of god were visualized in different pictorial creations whose language was derived from the time. Something comparable happens in the picture language of the Bible – my example of the apple and the snake plays on this.

But which elements of our present day life can serve as an expression of what exists beyond time? And how are these communicated?

This is a question which has concerned me for a long time and which eventually led me to the X-ray image.

For over 100 years this technique has been used to gain images of the invisible inside of our bod-ies. At first this was what interested me in addition to the equally fascinating aesthetics of X-ray images. Because here I perceived a parallel to what art means to me: a visible formulation of in-visible content.

Most things that move man are invisible in one way or another. Of course a facial expression, for example, mirrors an emotion or a thought, but it relates to this invisible thing like the famous tip of an iceberg.

Apart from this, what X-ray images show undoubtedly exists. They are images of something which is known to everybody who has heard of the process and in this respect it is possible to generally comprehend the content selected and named by me.

What interests me about the X-ray image is that something invisible comes to the fore as does the generally comprehensible, and is directed towards man. Within the framework of this knowl-edge, the opportunity arises for me as a painter and artist to focus on aspects of being human as a central theme – with the help of X-ray images.

Yet I have no interest in medical diagnosis – otherwise the main reason for using this recording technology. This may, in reference to the example image I chose earlier, be comparable to the biblical perspective of the fruit of knowledge. Here, too, it is of little importance whether it was a fig or an apple (there was once a theological debate over this) and it does not matter at all whether the apple handed to Adam by Eve, in a forbidden way, was of the Boskop or the Cox Orange variety. The far-reaching consequences of this “handing over of fruit” are independent of the concrete image but they have at the same time been expressed in it. (L.G.)

The first is daylight from the old church windows which admit a diffuse but special light. The basic lighting comes from nine ceiling lights which are arranged according to a series of musical notes from the piece “Ayre” by John Blow. Blow’s sound sequence floats over the room accompanied by the lighting effects. For the third special lighting alternative Fischer installed yellow glass panels, lit from behind and measuring 195 x 107, in the wall next to the seating rows. On these are printed verses from the bible. The panels appear like doors into adjacent light spaces which shine across, through the words of the gospel floating in the room. The emanating light has a meditative and mystic quality. The artist succeeds in creating a fitting sensual correlation between the word of God and light. Both of the artificial light sources can be adjusted separately.

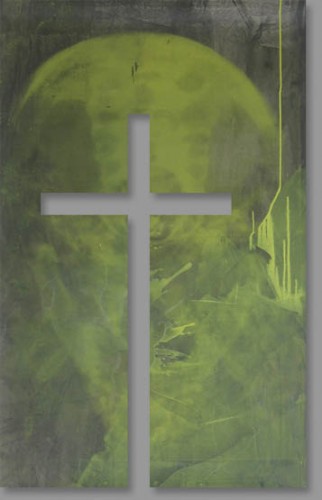

An x-ray image was also the starting point for the work on which the cross is based.

This x-ray is screen-printed onto a grounded drawing board (118 x 115). Pictured are man’s inner spaces in the head and spine. Parts of the picture were then superimposed with painting or blurred and changed to create other image levels. The artist then cut a cross from this picture, whose remaining negative form thus became part of the representation of human inner life. A cross-shaped hole is created in all image levels, reaching beyond the picture and thus beyond human existence. The cross also joins the picture more intensively with the room and thus also with those who enter it.

The aesthetic and theological high-point of Bernd Fischer’s room which is enormously successful on both creative and meditative levels, is encompassed in the “cross image”.

(L.G.)